(Warning: This will still be a math-heavy post.)

The contest went well! We had around 400 participants from across the US participate, which was pretty close to what we expected. There were only a few minor hiccups, but other than those, nothing terribly awful (like awful enough to end the contest early) happened, which is great.

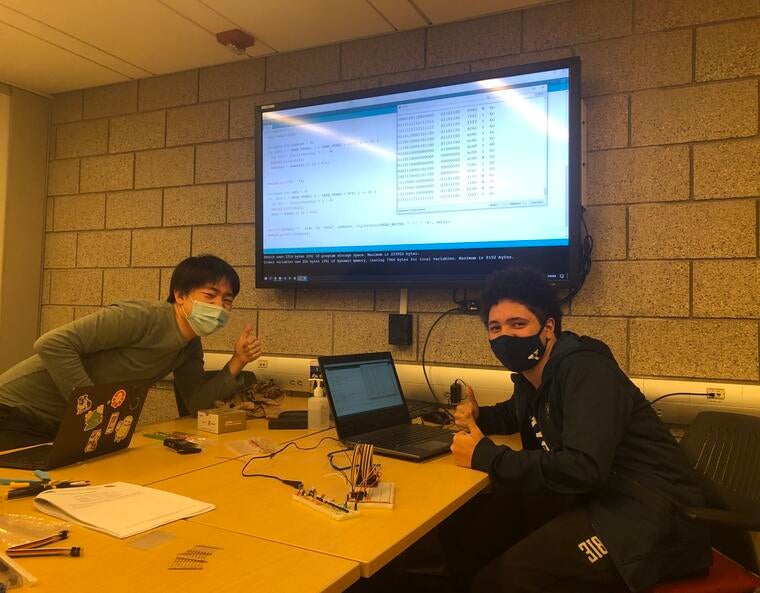

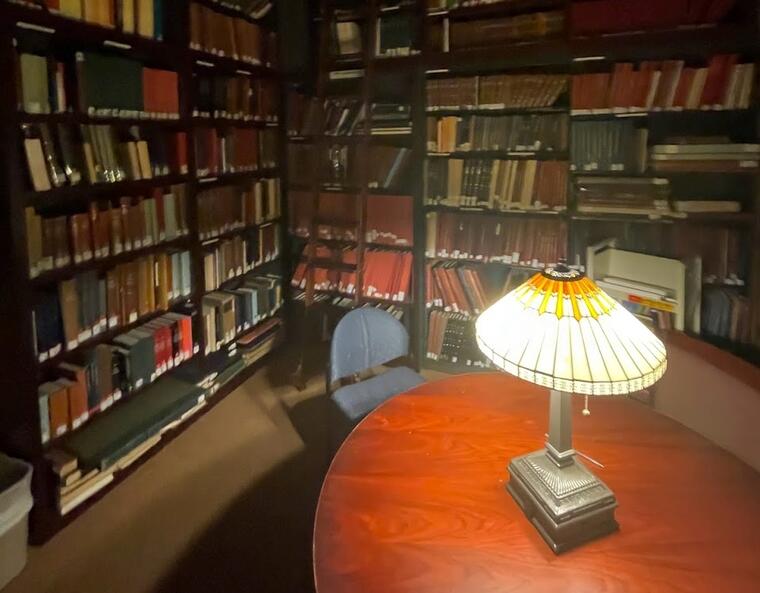

We met outside Marsh Auditorium at about 8:30 AM on a rainy Saturday morning to group together before the competition. From there, we decided to meet in some classrooms in the Yale Science Building to quickly go over the competition (which had a pretty nice view - see the cover photo) and get settled for the next few hours. My good friend and co-organizer Miles bought some McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches for us before the competition. Thanks, Miles.

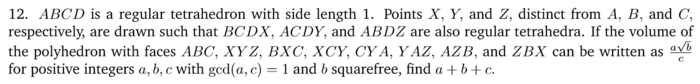

First up was the Mathathon round, a collection of seven sets of three problems (ordered in increasing difficulty) for teams of six or fewer students to solve in 60 minutes. Each team can only work on one set at a time; after they are done with their set, they have to submit it to get the next set. A few of the problems I wrote made it onto this round! Here’s one of my favorites:

I did not provide the diagram for this problem, which is a great way to slightly lengthen a problem and make it a tiny bit harder. I won’t write out the full solution here, but a key observation is drawing the line segment and that

. The numerical answer to this problem will be in the next MMATHS post.

Unfortunately, one of the problems we wrote had an issue that made it technically unsolvable, creating a dilemma: do we drop the problem or make an on-the-fly adjustment to make it solvable? We chose to drop the problem, since no adjustment could be made to keep the answer the same (the problem was actually solvable if you made an assumption that we thought was true ). But this raiseed more dilemmas: do we give an extension to make up for the lost time? Do we keep the score for the people who solved the question? We decided not give time and to drop the score. People literally could not have worked on the problem had they noticed the error, and since not everybody had gotten to the problem yet.

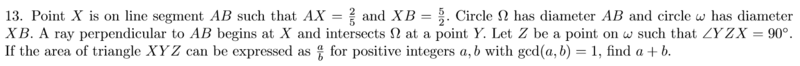

After the Mathathon round was a short break, then the Individual round, where students work independently to solve 12 problems in 75 minutes. I wrote the hardest problem on this test, and a grand total of 0 people solved it! I am both happy and disappointed by this— being a bit unconfident in my math skills, I was glad to see that I could still produce a difficult problem that stumped quite a few people that are much better at competition math than I ever was as a high schooler. However, I’m disappointed that nobody solved it! I genuinely don’t think it’s a challenging problem (OK, maybe it’s a bit computationally heavy, which is a problem since the only tools participants were allowed to use were pencil and paper), so I’m going to try and explain it, probably in the third and final MMATHS post. Instead, I’ll outline the rest of the competition, but not before giving you a chance to try the problem for yourself:

When the Mathathon round concluded, we planned to have a guest speaker. Of course, things never went according to plan, and the following Series of Unfortunate Events (a top-tier book series, by the way) happened: a while ago, we reached out to our planned guest speaker, who didn’t respond for a while to an email one of us sent to confirm the time for the talk (it later turned out the email never sent for some reason). Concerned, the person who sent the email asked two other contest organizers to reach out to the speaker; although they agreed to do this task, they never did, and by the time we reached out again, it was too late. I’m not naming anybody in this tragic tale; it’s unproductive and unfair to call people out publicly, and there were many other things we as a team should have done earlier. But if you were one of the two people who promised to reach out (and you know who you are), shaaaaame.

So, what does one do when they have to fill a newly-opened-up time slot? Well, the path we chose to take was a discussion of the individual problems by the problem writing team! This was fun, but also problematic for me because it meant I had to think of what to say about the problem I wrote and present it in an acceptable manner. I… somewhat managed to do this, I think? Because I was nervous and decently underprepared, I skipped through a lot of details and ended up drawing VERY shaky diagrams, but I feel like I gave a decent explanation. Oh well.

The final round of the competition was the Mixer and Tiebreaker rounds, which are held simultaneously. The Tiebreaker round contains 4 problems, and the top few contestants from the Individual round are invited to take it to determine an overall individual winner. This round is time-based; if there is a tie in terms of answers correct, then the contestant who submits first will place above the other contestant.

While all that’s going on, the people who don’t qualify take the Mixer round, which consists of 12 problems to be done in 45 minutes. The teams are scrambled (hence the name), so participants get the great opportunity to meet new people on top of doing math! How fun.

When those rounds were over, there was a Yale student meet-and-greet, where the participants got to choose one of us to talk about college with through Zoom breakout rooms. It was great getting to answer a few questions from curious high schoolers, and I hope I persuaded some math people to come to Yale and write problems for us, since we are woefully understaffed.

Finally, after the meet-and-greet was over and the results were tabulated, we announced the results, and the contest was over! By the time the contest concluded, it was already past 4 PM and we were all exhausted, so we went for a group boba trip to celebrate. Here’s my order:

An Oreo Creme Brulee Boba, from Whale Tea. It was tasty.

And that was how competition day went! The next (final) post: some more general thoughts on how competitions are organized, some solutions to the problems here, and some things I learned from the experience.

(Note: the answer to the problem from the previous MMATHS post was .)