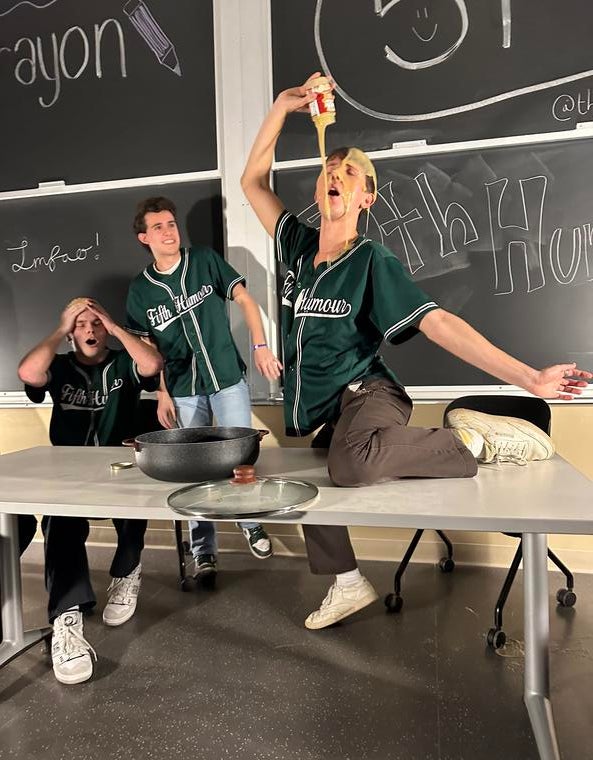

Walking into class on Wednesday, I was greeted by two friends. But today was unlike other Wednesdays, for these two friends had their hair braided together by some 6 feet of hair extensions, laced with white ribbons and connecting at four different points. The two were literally tethered to each other and had spent the entire day linked by these long locks, moving across campus as a cohesive unit.

Welcome to THST 339, otherwise known as “Advanced Performance Art Composition: Collaboration, Collusion, Collectivity” within the Theater and Performance Studies (TAPS) department at Yale. I am not a TAPS major, but I’m currently taking this course to learn new ways of expressivity and break up my more standard course load with something fresh and exhilarating. All of my classes at Yale feel special — whether that’s because of a charismatic professor, particularly interesting content, or the diversity of people that it draws in — but the academic eccentricity of THST 339 definitely makes it stand out above the rest.

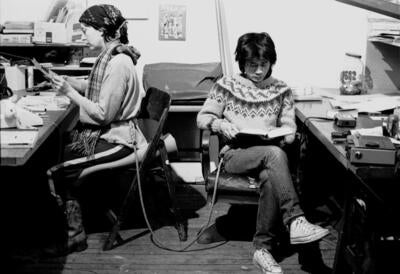

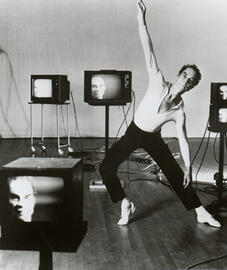

On this given Wednesday, we were performing pieces inspired by the concept of “duos” and what defines a “duo performance.” This assignment was part of a larger unit that focused on prominent duos within the performance art world, and we were guided to draw inspiration from various texts and performances we examined and engaged with as a class. The friends with their hair braided together had been influenced by the work of Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh, the artists involved in “Rope Piece,” who were joined together by an 8-foot rope around their waists for a full year from 1983-1984. Meanwhile, the piece I performed in class was inspired by legendary 20th century artists John Cage and Merce Cunningham, whose unique relationship between music and dance was (hopefully) reflected into my audio-visual presentation.

Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh in “Rope Piece” (1983-1984)

Pioneer of Modern Dance, Merce Cunningham.

The assignment prompted us to reconsider all our assumptions about duality and what a “duo” piece can entail. Do we need two performers to be considered a “duo”? What does that say about our relationship to the audience: can the spectator act as half of a duo? When we build upon past work, are we making a duo out of that artist’s creation and our own?

These questions are prodded, played with, and poked at over the four-hour class. Many sessions, I leave with more questions than answers! In an environment that invites experimentation, however, I can’t be surprised. Our next unit moves from the idea of the “Duo” to that of the “Collective.” I’ve already begun researching artists’ collectives like the Otolith Group, Elevator Repair Service, and Red New Order, and I can’t wait to see what projects my classmates bring in. I wonder if the next time I walk through the door to THST 339 more than two people will have their hair braided together…

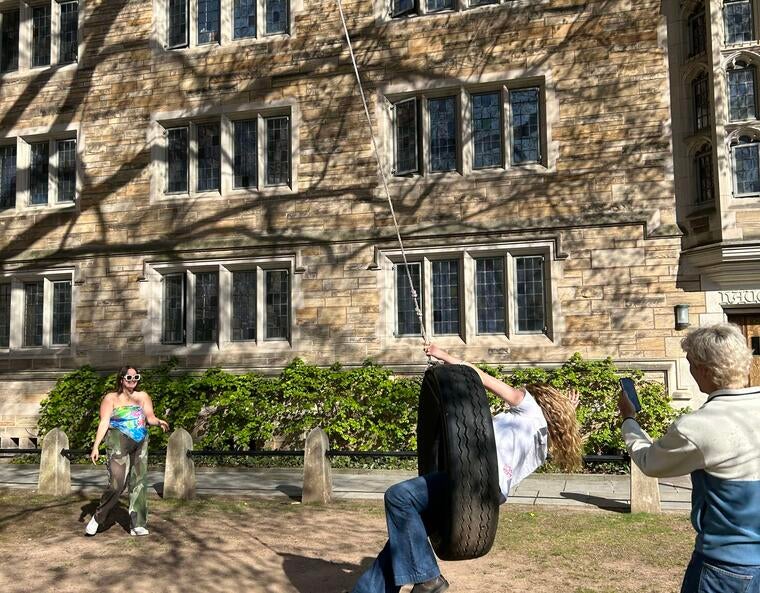

My point of view while participating!