As a writer, I’m always looking to test the boundaries of what I think is possible within any one given genre — and of what I’m capable of pulling off within it, too! And with Yale being Yale, there’s never been a shortage of classes (or classmates) who push me to do just that.

So this spring, when I learned about a course titled ENGL 464, “Diggin’ in the Historical Crates: Breathing Poetry into the Archives” taught by Pulitzer-winning poet Professor Tyehimba Jess (whose own work I’d read and performed in high school!) I leapt at the chance to enroll in it!

Over the span of thirteen weeks we read and discussed research-heavy and historically-concerned poetry collections, wrote poems in response to and in conversation with archival material, edited each other’s work, took trips to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library to look through archival materials like newspapers, photographs, and letters, and at the course’s end, compiled our work into our own chapbooks (in my case, read: a hastily printed and stapled but still carefully crafted group of twelve poems).

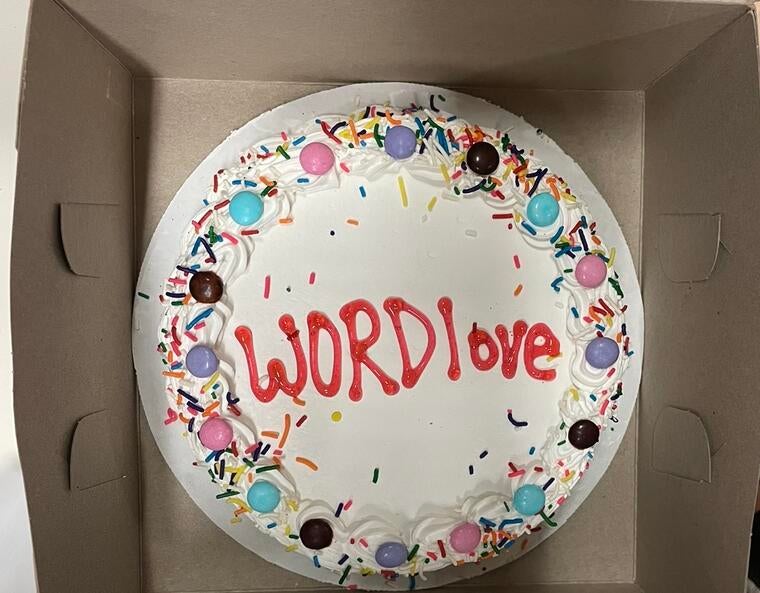

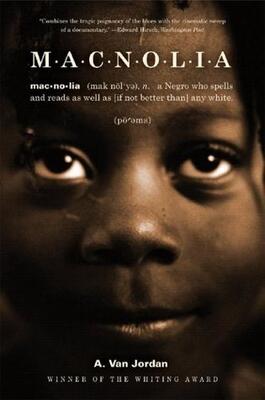

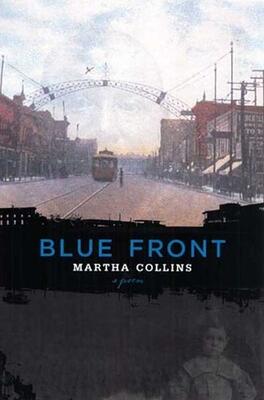

Some of the books we read for the course!

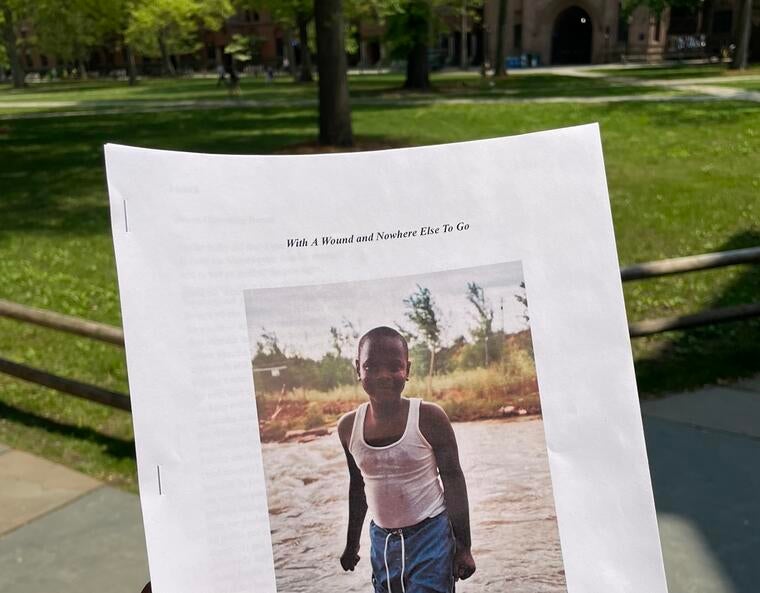

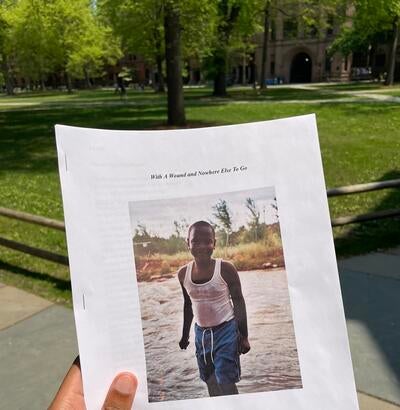

The front page of my collection of poems that I wrote for the course, dedicated to my cousin Elvis who appears on the cover!

The content of those chapbooks was entirely up to us, too! Spanning a wide range of topics, each person in the class focused on a subject of their choosing: the history of air conditioning and hotels in the Philippines, trans healthcare, Madam C.J. Walker, bird conservation and taxidermy, and medical racism and malpractice, to list a few.

And if it’s one thing about Professor Jess? He’s gonna write in an unconventional form — and ask us to experiment with the structure of our poems, too!

Throughout the semester, my pen (and my mind) were bent in several new directions as we wrote in a variety of forms: some sonnets (to oversimplify, 14-liners), golden shovels (where the ending word of each line in the poem corresponds to a word from a quote or a line from another poem), syllabics (where each line in the poem either has the same number of syllables as every other line, or the poem’s lines all have repeating, syllable-constricted patterns), and I even briefly attempted and then quickly abandoned a sestina (I refuse to explain how this monstrosity works, just know that it’s a difficult form to write in, it resoundingly defeated me, and I don’t want a rematch for a very, very long time — maybe even never).

The course was as challenging as it was illuminating, too! One of our assignments was to write a whole *crown* of sonnets, and I almost gave up halfway through the third poem in the series!

Ultimately, though, it became more than just a creative writing class or a poetry workshop — but also a place to think about what other ways of consuming, teaching, and recording history exist. As Professor Jess mentioned at one point thinking of himself as a historian who uses poetry rather than academic nonfiction to tell stories, I thought about how poems could be their own kinds of (unconventional, but hopefully, more accessible) historical records — and about what histories I might seek to preserve when I write my own books someday, too.